In recent years, researchers have become increasingly interested in educational and institutional strategies to limit or eradicate contemporary forms of racism in the United States. They have generally accepted that most people in the modern-day United States do not actually want to be racist, but the various legacies of oppression live on through American institutions, promote unconscious biases, and manifest in unintentionally racist behaviors. However, previous research has largely overlooked the interactive relationship specifically between insidious racists, and the institutions meant to limit and punish their intentional behavior. Insidious racists are conscious of their racist beliefs, they engage in intentional acts of racism, and yet, they hold value in not being deemed racist by American society. In this article I develop a framework of the varying institutional constraints associated with addressing insidious racism. I then deploy this framework on national and local case studies to highlight the contribution of this work. The national case study analyzes the institutional constraints that allowed for loan officers to engage in racist actions leading up to the Great Recession. The local case study analyzes institutional constraints that led to the deviant behavior and racist redistricting efforts coordinated by members of the Los Angeles City Council. Taken together, I show that institutional design and administrator ideologies determine the levels of insidious racism prevalent in a given institution.

Since its origin, the United States has created a legacy of oppression through centuries of slavery and racial oppression. The U.S. has passed many anti-discrimination laws, and as a society, has condemned discriminatory behavior on the basis of race, color, and national origin. As such, overt racism has declined over the last 6 decades- especially discrimination in the de jure form (Johnson et al. 1995; Dovidio and Gaertner, 2000). However, this American legacy of oppression remains relevant in individuals and institutions today, especially in the form of insidious racism. Insidious racism is a subtype of intentional racism that is engaged subtly instead of overtly. Investigations into the role of institutional constraints in preventing and addressing insidious racism have been overshadowed by extensive research on the various forms of unconscious and implicit forms of racism. In the present study, I describe a framework for the interactive relationship between insidious racists and the institutions meant to limit and punish their insidious behavior.

As previously mentioned, numerous studies have investigated the many types of contemporary racism that continue to play a prominent role in the lives of Americans, such as aversive racism (Gaertner and Dovidio, 2005), laissez-faire racism (L. Bobo et al. 1996), symbolic racism (Sears and Henry, 2003), and color-blind racism (Bonilla-Silva and Forman, 2000). These types of contemporary racism have been revealed through manifold experimental and survey analyses across decades, and have shown that many White Americans hold implicit prejudices that are showcased subtly and differently across various situations (Saucier et al. 2005). While the prevalence of these forms of racism are well-defended, they all focus on unintentional racism, to the extent that people don’t actually want to be racist. As such, research has often been focused on methods of education and exposure to eradicate these forms of racism (Neville et al. 2014). Concomitantly, these types of unintentional racists have historically been contrasted with the overt racists that are openly bigoted (Kovel, 1970). Thus, racists are typically categorized into two buckets: unintentional racists and bigoted racists.

In this article, I posit that the modern-day, bigoted racists have undertaken an insidious approach to racism, and I model the institutional constraints to addressing this form of racist behavior. The intentionality of this form of racism differentiates insidious racism from other subtle forms of racism, such as symbolic, color-blind, and aversive racism. Further still, insidious racism goes beyond the capitalist exploitation of races due to the disproportionate relegation of people of color into lower classes (L. Bobo et al. 1996). Instead, insidious racism draws on the negative construction of people of color (Gilens, 1999), and that negative construction has continued political and economic consequences in an America that has institutional constraints.

This article proceeds as follows. The first section provides a thorough analysis of the various forms of racism and outlines how insidious racism is the chosen form of modern-day bigotry. The second section models the prevalent institutional constraints that limit the ability of American enforcement agencies to address insidious racism. The third section provides a national example of the institutional constraints on addressing insidious racism through analyses of cases filed against Wells Fargo in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The fourth section provides a further example via a recent case study of insidious racism through an analysis of the 2021 redistricting efforts in the city of Los Angeles, California. Finally, the article concludes with a summary and possible ways forward for future researchers.

Throughout US history, the conceptualization of race and the engagement of racism have evolved to create a spectrum of racially discriminatory behaviors and beliefs (López, 2006). In this section, I consider the extent to which conventional theories of racism explain the institutional constraints that limit societal protections from insidious racism in the United States. Specifically, I show that conventional theories of racism do not critically assess the role of institutions in handling the actions of intentional racists that engage their racism discretely. These conventional theories include aversive racism, laissez-faire racism, color-blind racism, and symbolic racism. I label these as conventional theories because they all attempt to explain racist behaviors, beliefs, and policy outcomes in a time period when overt racism has been legally banned and socially frowned upon. My goal is to use the deployment of these conventional theories of racism in past scholarship to showcase how they can answer questions of modern-day racist behaviors, and also reveal the types of racist behaviors, which they are ill-equipped to expose and address (Williams, 2019).

Aversive racism theory was first elucidated in 1970 with reference to White racists, and differentiated itself from more popular theories of “dominative racism” (Kovel, 1970). Dominative racism is the expression of bigoted, racialized acts performed by bigoted racists. Aversive racism stems from the notion that racist actions are not necessarily limited to bigoted racists. Instead, White people who are well-meaning and don’t want to be prejudiced might actually act in prejudiced ways due to implicit biases they acquired from living in their society (Gaertner and Dovidio, 2005). These individuals harbor egalitarian beliefs, and as such, they are intentional about limiting any unjustifiable displays of prejudice toward other races. Unfortunately, however strong their egalitarian beliefs may be, they may still hold implicit negative feelings toward racial outgroups (Dovidio et al. 2016). Put another way, White egalitarians, for example, may find Black people (members of a racial outgroup) “aversive.” Further, these White egalitarians may also find the idea that they might actually be prejudiced “aversive” as well. As such, these individuals will not express blatant acts of racism, but might engage in a more subtle form of racism that allows for their self-image as progressive egalitarians to remain intact. These subtle forms of racism can impact aid to racial outgroups (Henkel et al. 2006), employment decisions of candidates within a racial outgroup (Son Hing et al. 2008; Dovidio and Gaertner, 2000), and criminal convictions of members of racial outgroups (Johnson et al. 1995).

Laissez-Faire, Color-Blind, and Symbolic Racism are theories that generally refer to racism grounded in the denial of the present-day ramifications of centuries of racial oppression. The differences between these theories are so subtle that Bobo, a leading scholar of laissez-Fare racism, claimed that the primary reason he continues to use the term “laissez-faire racism” over “color-blind racism” is because he believes using “color-blind” is a “dubious analytical strategy” that obfuscates the concept (L. D. Bobo, 2017, pg. 91). Other authors suggest that the three types are interchangeable (Burke, 2016).

Laissez-faire racism revolves around the idea that Black people were put into a terrible socioeconomic position by the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow. As such, when America experiences negative economic shocks, Black people have been (and continue to be) situated in such a way as to have worsened impacts across all socioeconomic classes (L. Bobo et al. 1996; Thompson and Suarez, 2019). The theory of symbolic racism describes a continuing resistance to racial equality in the post-civil-rights era. The general idea is that the demands of Black people and providing them with advantages are unwarranted because Black people are continuously disadvantaged because they don’t work hard enough (Tarman and Sears, 2005). Symbolic racism operates as the politicization of the conservative belief in low levels of Black individualism (Sears and Henry, 2003). Color-blind racism examines individuals and institutions that ignore the impacts of historical and overt racism, and instead charge racial inequities as the fault of inferior cultures (Bonilla-Silva and Dietrich, 2011). The logic of color-blind racism argues that White people use color-blind racism to express their racial dominance as the result of hard work and not centuries of racial oppression, and Black activists have advocated against this narrative for decades (Charmichael, 1966). While the logic is similar to symbolic racism, color-blind racism differs in its level of analysis; it looks more at collective group positioning as opposed to the individual-level prejudice.

These conventional theories of racism come together to explain the various ways that legacies of overt racism have maintained their influence in American society. However, their primary focus has been on the behaviors of those individuals (mostly White people) whose racism is not subject to a monitored demand for equitable behavior. Aversive racism studies have found that, many White individuals will unintentionally utilize societally-accepted excuses to engage in racial discrimination. Specifically, the White individuals did not appear to be aware that they were filtering their decisions through internalized racist beliefs. On the contrary, they believed they were operating indiscriminately (Saucieret al. 2005). This scholarship has been extended to the discriminatory decisions of jurors (Johnson et al. 1995) who justify their discriminatory behavior on the grounds that they were not letting a guilty person go free, as well as hiring officials who amplify the positive qualifications of White applicants and amplify the negative qualifications of the outgroup members (Son Hing et al. 2008; Dovidio and Gaertner, 2000). Equity-centered educational programs, as well as exposure to people of color, have been shown to reduce levels of this type of unintentional racism in communities (Neville et al. 2014).Taken holistically, aversive racism helps explain expressions of unintentional racism and how to diminish them, but relatively little is understood about the obfuscations of true racists who do not want to incur the social costs of intentionally racists acts.

The intentionality limitation also persists with the additions to conventional racism theory brought by the tenets of laissez-faire, color-blind, and symbolic racism. These conventional theories can explain prejudiced attitudes toward Black people, and can explain how these attitudes are rooted in the legacy of racial oppression in the United States. These scholars posit that institutions can be race-neutral, yet still perpetuate racial hierarchies and White supremacy through the avoidance of retribution for centuries of oppression. A prime example of this is found in the ubiquitous discussion around the Black-White wealth gap, which has worsened since the Civil Rights era (Wolff, 2021; Oliver and Shapiro, 2006). One of the primary explanations of laissez-faire racists is that Black people do not work hard enough to close the wealth gap, and racial prejudice is not a primary barrier to wealth accumulation. These explanations fail to acknowledge the intergenerational role of disparate wealth accumulation as the result of racist policy (Oliver and Shapiro, 2006; Hamilton and Darity, 2009). Instead, as color-blind theorists explain, these racists imagine Black people with poor work ethic as a result of inferior cultures (Bonilla-Silva and Dietrich, 2011). This pull-yourself-up-by-your-own-bootstraps view of Black Americans persists in the societal conversation around racial wealth inequality, even though, in order for Black people to bridge the wealth gap themselves, growth in Black wealth would have to outpace White wealth by 100% for 20 consecutive years (a feat not even achieved by Warren Buffet). Footnote 1 Despite this financial fact, laissez-faire racists would argue that Black people as a group can do better by “working harder.” Interestingly, studies have shown that there is no difference between White and Black wealth appreciation for those families that have positive assets (Hamilton and Darity, 2010; Darity and Mullen, 2020). As such, the work-harder narrative of laissez-faire racist is an all-around unfounded claim that persists due to internally held prejudices.

Still, the belief system of these color-blind racists does not necessitate racist behaviors, but is sufficient for racist behaviors to occur. Previous research has shown that the existence of color-blind racism lays the foundation for the perpetuation of racism through evasiveness within relatively progressive organizations ((Beeman, 2015), through the construction of marginalized communities as pathological (Ray, 2023), and through disenchantment with nonstandard tactics of producing positive social change (Beeman, 2022). While these are unintended outcomes produced by people who would claim to be race-conscious (Ray, 2023, 202; Beeman, 2022), an assessment of intentionality is still a limitation. Strategies to address the impacts of laissez-faire, color-blind, and symbolic racism do not address the pitfalls of hidden and intentional bigotry, and this is the primary focus of this article.

As previously outlined, insidious racism is a form of overt racism that provides for the existence of many individuals and institutions that are currently intentional in their discrimination, unfavorably, against people of color. For decades, many works have revealed that there is an abundance of overt racism that is deliberately kept out of public view, such that modern surveys would not capture it (Wellman, 1977). For example, a study of White college students across the United States shed light on the ubiquity of racist jokes, racist statements, and racist teaching within the “backstage,” which are private settings that White people deem are “safe” (Picca and Feagin, 2007). The present study leverages these previous works and reveals the damage of this overt racism in the backstage, specifically when it leaks into the creation or implementation of policy. Insidious racism extends beyond the perpetuation of racist beliefs in the backstage, and even extends beyond racist social norms that covertly limit access to opportunities for marginalized racial groups (Coates, 2008). Insidious racism assesses the pernicious incorporation of racist beliefs into policy, such that the weight of the law leans heavily in favor of an oppressive racial hierarchy.

This framing of modern-day intentional or dominative racism fills the intentionality gap in the literature on conventional racism highlighted above, and provides for an acute analysis of the institutional limitations to address it. The inclusion of intentionally subtle racism to the suite of conventional racism allows insidious racism to exist alongside of, and separate from aversive, laissez-faire, symbolic, and color-blind racism. Insidious racists hold conscious beliefs of racial inferiority, and act on those beliefs. However, the insidious racist’s actions are dependent on the allowances of the person’s relevant institutional settings. While other forms of racism also depend on the structures of political and economic institutions (Feagin, 2013), insidious racism relies on the intentional and strategic behavior of individuals that seek out and racially exploit these institutional structures. The intentional exploitation of institutional structures is outlined in greater detail in the next section.

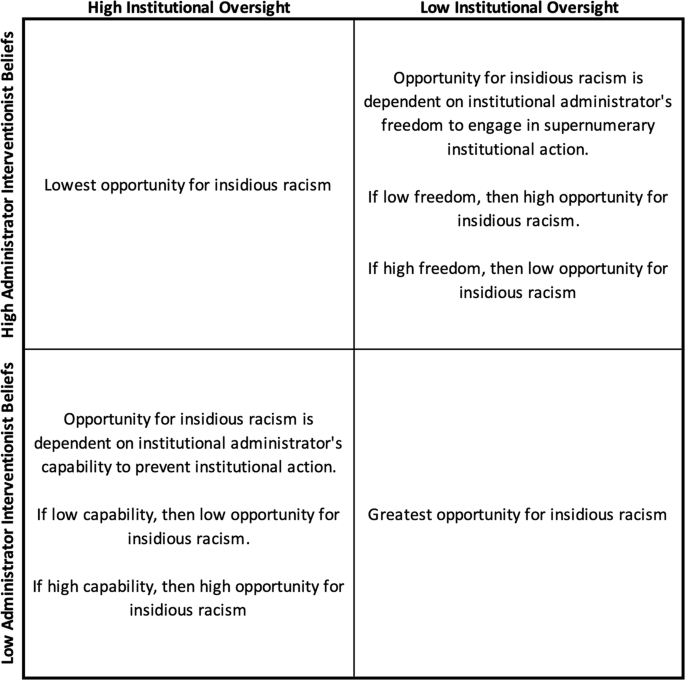

I theorize that the level of racism experienced through institutions is dependent on two factors: the institutional setting and the ideologies of an institution’s gatekeepers. Particular mixes of institutional settings and gatekeeper ideologies create environments where racial exploitation can occur. Insidious racists will recognize these environments and exploit them. Specific to political institutions in the United States, I first expect that institutions with low levels of government oversight will experience higher occurrences of intentional and strategic racism. That is, political institutions developed from the ideological framework of low government intervention will axiomatically deliver less oversight against racism because they, a priori and generally, minimize accountability and oversight of actors and actions taken. Second, I expect that an institution’s administrators will influence the levels of insidious racism, dependent on the administrators’ ideologies around governmental or institutional interventionism. Through analyses of cases filed against Wells Fargo Bank following the Great Recession, as well as racial animus within the Los Angeles City Council, later sections of this article showcase how variances in institutional oversight determine the presence of intentional racism.

The level of governmental oversight provided to fight against racism within an institution (whether congressional, bureaucratic, or judicial) varies by institution. This variation is based on institutional design and on political-institutional setting. Because institutions are human creations, their designed constraints reflect their creators, or broad coalitions that found it prudent to change the institutions (Jeong et al. 2014; Binder and Smith, 1998; Grafstein, 1988). Institutional design, as it pertains to oversight, can provide for an active monitoring of an institution’s practices to prevent bad actions. Alternatively, institutional design can provide for internal mechanisms within an institution that alert the institution’s administrators of discrimination issues. These two types of oversight, dependent on institutional design, are called “police oversight” and “fire-alarm oversight” respectively (McCubbins and Schwartz, 1984). Further, when designs for institutional oversight are enacted or changed, the enacting coalitions toggle design features to strategically increase the political cost for amendments by future coalitions (Pierson, 2000; Wood and Bohte, 2004). As such, oversight designs that are insufficient to monitor and prevent inequity are subject to lasting exploitation, not quickly addressed or altered (Orren and Skowronek, 2014).

Theoretically, insidious racism posits that the level of oversight employed by political institutions determines the opportunity structure for intentional racism. I define level of oversight as the extent to which a given institution is monitored, as determined by policy, to ensure fair practices. Thus, the level of oversight over an institution can vary depending on the specifications of the governing policy. For example, in the policy realm of home foreclosures, some U.S. states currently require financial institutions to go through an in-court process to foreclose on a home (judicial foreclosure), while other states provide for an out-of-court process (non-judicial foreclosure) (Ghent and Kudlyak, 2011). As I employ here, the level of oversight is deemed higher in a state that requires institutions to go before a judge when foreclosing on a home (Roberson, 2024). The designs and operations of institutions are often influenced by the political settings in which they are developed, which is why political-institutional setting helps explain variations in similar institutions located across the United States (Ghent, 2012). A high level of institutional oversight works as a road block against racism, whereas a low level of institutional oversight provides a path for racism to occur. Further still, the racial status quo is more than just aggregated attitudes and behaviors of individuals – it is also the structure and organization of institutions. As such, the effectiveness of institutional oversight at inhibiting discrimination is subject to the design of the institution with respect to equal opportunity and fairness.

The other determinant of the opportunity structure for insidious racism is the interventionist belief system of the institutional administrators. Party ideologies inform individual beliefs on the triggers, scope, and frequency of government intervention in the dealings between Americans and American institutions (Gerring, 1998). These ideologies, and their concomitant interventionist belief systems, can have substantive impacts on the actions (or inaction) of governments: the ideologies of political appointees can sway the outcomes of federal bureaucracies (Clinton et al. 2012), judiciaries can determine outcomes based on ideology in cases where the law is unclear (Sunstein et al. 2006), and U.S. presidents can strongly influence the extent to which government agencies engage with the U.S. population (Clinton et al. 2014). Extending the previous example of state foreclosure laws, prior research has found that the interventionist belief system of judges are strong determinants for which party will prevail in a foreclosure case that goes through the court system (Roberson, 2024). When the government is called upon to provide oversight on issues of race, these interventionist beliefs become very important in determining political and economic outcomes of racialized groups, especially when the administrators have more flexibility in their actions (Hinkle, 2015).

The administrators are the human actors charged with monitoring an institution and the institution’s executions of its function, and their set of possible actions are limited by their relevant institutional design (Krause and Cohen, 2000). The interventionist belief system of the institutional administrators references the degree to which an administrator believes government intervention into social affairs is appropriate. The exposure of the American public to dramatic shifts in administrator oversight are the result of decades of ideological partisan-sorting, through which the American electorate and Congress has become more polarized (Mason, 2015; Thomsen, 2014; Druckman et al. 2013). Comparatively, district judges may be the administrators of institutions wishing to engage in home foreclosure, offering increased stability in administrator beliefs due to the infrequency of judge replacement. If an administrator believes in little to no government intervention into the private lives of citizens and businesses, there will be a greater opportunity for insidious racism to occur in the administrator’s institution. Figure 1 shows the relationship between institutional oversight, administrators, and insidious racism.

There are 4 key theoretical assumptions with insidious racism:

When America catches a cold, Black America gets pneumonia,” is a ubiquitous adage within the Black community (Baradaran, 2017). This Black proverb was particularly on point in the aftermath of The Great Recession, which disproportionately devastated Black and Latino communities, and insidious racism was a primary culprit (Bhutta et al. 2020; Dettling et al. 2017). As many families lost their homes, many families from communities of color wondered if it had to be this way. Previous studies have shown that race played a primary role in this foreclosure crisis, where Black people were 80% more likely than White people to receive subprime loans after accounting for credit scores, incomes, loan-to-value ratios, and neighborhood characteristics (Jayasundera et al. 2010; Bocian et al. 2010). These subprime loans, contrasted with prime loans, were dangerous financial instruments that led many down an expedited path to foreclosures. To show the institutional constraints of addressing insidious racism, I review cases related to Wells Fargo’s discriminatory treatment of people of color. First, I review the methods of case selection that led to an analysis of cases involving Wells Fargo Bank leading up to the Great Recession. Next, I explain the two types of mortgages and how they differ. I then explain how Wells Fargo Loan Officers were able to engage in insidious racism by providing subprime mortgage products to Black and Latino families, and outline how relevant institutional constraints limited intervention to prevent the occurrence of insidious racism.

In the previous section, this article explained the varying institutional limitations to addressing insidious racism, which was meant to explain how explicitly racists attitudes can have far-reaching impacts on modern-day behavior. Previous models show that individuals that do not express overtly racist attitudes would not perform overtly racist acts (at least not intentionally). These previous models do not adequately explain situations where individuals holding overtly racist attitudes engage in societal deception- that is, they pretend to be race-neutral when they are not.

I use the deviant case selection strategy as outlined by Seawright and Gerring (2008) to find a case that has an outcome that is different from what other theories of contemporary racism would suggest. I leverage the theory development above to identify the primary units of analysis to aid in case selection (Yin, 2003). In this case study, the primary units of analysis are organizations that, for one reason or another, lack de jure institutional oversight over operations where race has the potential to be used to alter the flow of resources. The deviant Wells Fargo cases illustrate the use of two variables under the theory of insidious racism (institutional oversight and administrator interventionist beliefs) that can be applied to similarly situated cases in the population of contemporary racism. Specifically, the Wells Fargo cases present situations where individuals operate under legal frameworks that demand race-neutral policies, but lack oversight or avenues for enforcement intervention. Current forms of contemporary racism would suggest that the racially discriminatory outcomes revealed in the Wells Fargo cases were due to implicit biases of the organization’s loan officers. However, the current deployment of the Wells Fargo cases helps explain, in context, how the design of lax oversight within institutions meant to prevent racial discrimination can lead to instances where individuals exhibit behaviors grounded in explicitly racist beliefs (insidious racism). To analyze the cases, I perform a textual analysis of opinions, memorandums, and orders from federal courts across the United States in the aftermath of the Great Recession, specifically involving alleged Fair Housing violations by Wells Fargo Bank.

The typical avenue to homeownership in the United States today is the fixed-rate mortgage (FRM) (Green and Wachter, 2005). The idea is basically that consumers can engage in reliable financial planning when their future mortgage payments are deprived of volatility. These FRMs are contrasted with other types of mortgage plans, most notably, the adjusted-rate mortgage (ARM). ARMs differ from FRMs because, as the name suggests, the interest rate on these mortgages fluctuate over time based on economic market conditions, which makes budgeting for mortgage payments much more difficult for the typical homeowner. FRMs are considered safer for the consumer due to the stability of their interest rate over time, and the federal government has successfully promoted FRMs through the existence of government-sponsored enterprises such as Fannie Mae (the Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation). On the other hand, ARMs have historically comprised about 11% of the share of mortgages, spiking only as high as 35% before the Great Recession of 2008 (Kan, 2022). ARMs are more beneficial to mortgage providers because the providers have the opportunity to take advantage of changing market conditions over time- a feature that is wholly unavailable to them if they are locked into a fixed-rate contract with a borrower (Green and Wachter, 2005).

Leading up to the great recession, to determine whether a potential borrower was offered an FRM or an ARM, creditors would assess the potential borrower’s risk of default. If a borrower’s risk-profile suggested that they had a low risk of default, then the borrower would be offered a prime mortgage- that is, a mortgage with a lower interest rate and/or required down payment. These prime mortgages were often FRMs with low-interest rates or ARMs with intentionally low volatility in interest rate fluctuations over time. In the event that a borrower had a risk profile that was impaired or classified them as high-risk borrowers, creditors might have offered them subprime mortgages. Subprime mortgages were most often ARMs that would provide borrowers with low initial monthly payment by employing a low “teaser-rate.” However, once the teaser-rate period ended, the monthly payments would increase dramatically, often times far exceeding the budget of the borrower (Dickerson, 2014). Further, leading up to the Great Recession, many of these subprime mortgages were equipped with other problematic attributes, such as payoff penalties designed to lock borrowers into perennial refinancing relationships with their initial mortgage providers in order to maintain affordability (Lacy, 2012).

Racism also played a role in determining which potential borrowers were offered subprime mortgages or prime mortgages. As was mentioned prior, Black people were 80% more likely than White people to receive subprime loans after accounting for credit scores, incomes, loan-to-value ratios, and neighborhood characteristics (Jayasundera et al. 2010; Bocian et al. 2010). Court cases brought against Wells Fargo provide insight into how loan officers allegedly altered their loan offerings on the basis of race in a discriminatory manner. In a suit brought against Wells Fargo in Baltimore, Maryland, affidavits from Wells Fargo loan officers revealed a pattern of discriminatory practices in the company, including references to Black people as “mud people,” and subprime loans as “ghetto loans” (Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Wells Fargo Bank, 2011). In an interview with the New York Times, the nation’s top-earning Wells Fargo mortgage loan officer, Beth Jacobson, became a whistle-blower regarding Wells Fargo’s discriminatory behavior (Powell, 2009). She claimed that leaders at Wells Fargo allegedly viewed the Black community as primed for exploitation, as “working-class blacks were hungry to be a part of the nation’s home-owning mania.” Further, a case filed against Wells Fargo in Memphis alleges that Wells Fargo engaged in predatory lending practices known as “reverse redlining,” resulting in disproportionate foreclosures on homes in Black communities (City of Memphis and Shelby County, Plaintiffs, V. Wells Fargo Bank, 2011).

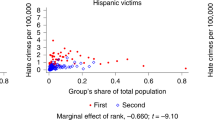

There were several other cases brought against Wells Fargo as well, including from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the cities of Oakland, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Philadelphia. These cases have either been settled without payment or admission of caused harm (Reckard, 2010), dismissed on the grounds of being too far removed from any potential harms (McKeown, 2021), resolved in summary judgement due to a lack of discrimination by Wells Fargo within the 2-year limitations period (Wright, 2015), or are still undergoing litigation in federal courts (Feinerman, 2018; Brody, 2018). While these cases have had varied procedural paths, all of the cases echoed the Memphis and Baltimore cases in their claims that the mortgage lender allowed for policies of racial discrimination in mortgage steering. Further, all of the Wells Fargo cases highlight ways in which intentional racism was at least the result of subpar oversight to ensure equity, even though disparate impact cases such as these are not designed to impose new policies on private actors. The most public of these cases resulted in the Department of Justice filing “the second largest fair lending settlement in the department’s history to resolve allegations that Wells Fargo Bank, the largest residential home mortgage originator in the United States, engaged in a pattern or practice of discrimination against qualified African-American and Hispanic borrowers in its mortgage lending from 2004 through 2009” (Office of the Deputy Attorney General, 2014).

The Wells Fargo cases outline a pattern of alleged racism that can only be described as insidious racism. The Wells Fargo loan officers leading up to the Great Recession were very intentional about their racism. Their actions were not guided by implicit biases, and the overarching mortgage system was not designed in a way that would, on its own, result in the level of subprime mortgages experienced by Black communities. Instead, the loan officers engaged in intentional racism that was not easily seen. Due to the financial commission structure that incentivized loan officers to increase their volumes of loan originations, the loan officers preyed on Black communities (Dickerson, 2014). The loan officers would even target Black churches because of their influence in the Black community, and would not reveal to Black borrowers that subprime loans, while available to them, were not in their best interest. This is especially problematic because professionals reveal that an applicant’s race was often a silent factor in determining the types of loans that applicants would receive (Korver-Glenn, 2021). To that end, many of the Black and Latino borrowers that were eligible for prime mortgages were discriminatorily supplied subprime mortgages. Because subprime loans could be provided with little to no paperwork, loan officers could increase their loan volume and take advantage of greater commissions by exploiting Black communities.

As outlined in Fig. 1, insidious racism is dependent simultaneously on the level of institutional oversight, the opportunity for administrator intervention, and the interventionist beliefs of the administrator. In these Wells Fargo cases, the level of institutional oversight leading up to the Great Recession was provided by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA). The ECOA was signed into law in 1974 and provided enforcement authority for national banks (such as Wells Fargo) via the Federal Reserve Board (CFPB, 2013; Matheson, 1984) before the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. The ECOA, as amended in 1976, bans discrimination in the credit market on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, marital status, age, or the receipt of public assistance.

To align with the goals of ECOA, The Federal Reserve Board implemented Regulation B, which required creditors to provide a report that details reasons for adverse actions on loan applicants (such as loan denials) (Gilkeson et al. 2003). The regulation was meant to provide awareness to consumers of potential discrimination, and thus pressure creditors to give everyone a fair shake. The consumers, if they believed there was discrimination, could enforce ECOA through private litigation.

However, there were situations where a potential borrower would apply for a loan, and instead of denying the loan, the creditor would provide a counteroffer with significantly worse conditions (such as an applicant applying for a prime FRM, but then counteroffered a subprime mortgage instead). If that counter offer was accepted by the applicant, Regulation B did not consider the deal as an adverse action (Matheson, 1984). Because these types of deals were not considered adverse actions, creditors were not required to provide borrowers who accepted the counteroffer with a report that explains the reasons as to why a counteroffer was proposed. In other words, this loophole in Regulation B severely undermined the regulation’s intention for consumers to provide oversight and enforce ECOA when they suspected possible discrimination. The Regulation B loophole provided for very low institutional oversight. Consumers in the counter-offer scenario were completely stripped of their discriminatory oversight function. Without this oversight function, there could be no private litigation, and thus no options for administrative entities (such as judges) to intervene or even become aware of the discriminatory behavior. Together, the low institutional oversight and absent administrator engagement created an environment with a high opportunity for insidious racism. The loan officers that were insidious racists were able to flourish by intentionally exploiting Black and Latino communities, and the eventual foreclosure crisis finally revealed their actions.

In order to further evince the existence and scope of insidious racism, I again turn to the deviant case selection strategy as outlined by Seawright and Gerring (2008). However, rather than focus on national policy, as with the ECOA and Wells Fargo cases above, I turn to localities and apply the same primary units of analysis developed in the theory section of this paper. The conjunction of national and local case studies is important in order to show the range of institutions that insidious racists can navigate, exploit, and intentionally cause harm. Similar to the Wells Fargo cases above, city councils traditionally have legal measures in place to limit group interaction outside of the public eye, specifically with the goal of limiting dishonorable actions by elected officials. As shown below, the Los Angeles case provides insight into the ways in which insidious racism might result in intentionally racist policy. To analyze this case, I perform a textual analysis of relevant legal oversight that governs the Los Angeles City Council, as well as the uncovered and vocally recorded plan of operation by insidious racists.

In October of 2022, a recording was released of a secret conversation that took place in the Los Angeles Federation of Labor between three Latino members of the Los Angeles City Council and the president of the Los Angeles Federation of Labor. Nury Martinez was the President of the Los Angeles City Council, Kevin de León and Gil Cedillo were city council members, and Ron Herrera was the President of the Los Angeles Federation of Labor. The leaked recording revealed how insidious racism can lead to behaviors that have direct and racialized political consequences. More acutely, by operating within the limits of California’s Brown Act, these elected officials were able to meet and discuss racist plans to undermine the voting power of Black Angelinos through the Los Angeles redistricting process. The exposure of racism through a secret recording of publicly egalitarian government officials bolsters the theoretical arguments of this paper, which contend that there is a level of racism that exists below the public radar, that is intentional, and that levies widespread political and economic consequences.

To illustrate how the scandal of the Los Angeles City Council members exemplifies insidious racism, I must first provide an analysis of the level of relevant institutional oversight. The Ralph M. Brown Act, commonly known as simply, “the Brown Act,” was enacted as a California state law in 1953 and has had several amendments since. At the time of writing, the law guarantees the public’s right to attend and participate in meetings of local legislative bodies. The law was originally authored in response to a growing concern that local governments were holding secret meetings, often without public notice or public participation. The Brown Act provides a variety of protections for the public, including requirements for giving public notice of meetings, allowing for public comment during meetings, and providing for open and accessible minutes of the meetings. As it pertains to the current case of these LA City Council Members, the Brown Act defines and limits what is considered a meeting (R. M. Brown, 1953).

“meeting” means any congregation of a majority of the members of a legislative body at the same time and location… to hear, discuss, deliberate, or take action on any item that is within the subject matter jurisdiction of the legislative body.

A majority of the members of a legislative body shall not, outside a meeting authorized by this chapter, use a series of communications of any kind, directly or through intermediaries, to discuss, deliberate, or take action on any item of business that is within the subject matter jurisdiction of the legislative body.

In the case of this meeting of elected officials, the councilmembers present did not make up a majority of the Los Angeles city council members. Further, the meeting attendees did not make a majority of council members on a particular committee either. Martinez and De León were both members of the LA City Council’s redistricting committee, but they did not constitute a majority because the committee had 7 members at the time of the recording. The limitations of the Brown Act provided enough wiggle room for the 3 members of the LA council to convene outside of the public eye and strategize. As I show below, their strategies were acutely racist, and because of the limitations of the Brown Act, when these elected government officials engaged in strategic and race-based planning, they were not subject to institutional oversight.

Based on an audible and written transcript of the recording published by the Los Angeles Times (Staff, 2022), anti-Black racism was woven throughout the conversation, which is a common feature when racists find themselves in a comfortable backstage environment (Picca and Feagin, 2007). The following quotes in this section are all direct quotes from this leaked audio recording. At one point in the leaked conversation, Nury Martinez, the president of the Los Angeles City Council, referred to the young adopted son of another member of the Los Angeles City Council as a little monkey. Specifically, she stated, “Ahí trae su [There he brings his] negrito, like on the side… Parece changuito [He seems like a little monkey].” The use of negrito and changuito were both racist terms when used to describe a Black child. Later in the conversation, the discussion turned to the potential endorsements of Los Angeles County District Attorney, George Gascón. Nury Martinez stated, “Fuck that guy. I’m telling you now, he’s with the Blacks.” Taken together, these direct quotes from the president of the Los Angeles City Council reveal a developed and conscious anti-Blackness (K. Brown and Jennings, 2022).

The anti-Black racism expressed in the leaked conversation was intentionally used to strategize around undermining Black power in Los Angeles. This racism was leaking from the safe environment of the backstage, and intentionally pooling into harmful policy. The decennial redistricting process in Los Angeles was largely on the agenda for the strategizing council members. Gil Cedillo stated that he believed Mexicans needed to “exercise their power,” and that “there’s 57 out of 60 seats that African Americans are in, are Latino seats.” The officials also discussed how they might redraw council districts to solidify Latino power, and remove power away from Black Angelenos (K. Brown and Jennings, 2022). As Gil Cedillo stated on the leaked recording, the officials were aware of “three seats” on the Los Angeles City Council that were held by Black Americans, and the group believed their districts could be redesigned to secure more Latino’s on the city council.

At the time of the leaked conversation (October 2021), Los Angeles was in the midst of its redistricting process as outlined by Section 204 of the Los Angeles City Charter (Healy, 2022). Aligned with the charter, a 21-member redistricting commission was appointed by elected city officials to advise the City Council on adopting an equitable council district map. In late October of 2021, the commission proposed a district map for Los Angeles. However, in November of 2021, the Los Angeles City Council, under Nury Martinez, adopted an amended version of the commission’s district map that was aligned with the racially charged conversation held between Nury Martinez, Gil Cedeelo, Keven de León, and Ron Herrera. These conversations around redistricting were consequential to the district map eventually endorsed by the Los Angeles City Council. The contemporary theories of racism cannot adequately explain the actions of these city council members, as their acts of racism were intentional and meant to remain secret. Taken holistically, this case provides support for the tenets of insidious racism, such that public egalitarians can consciously and secretly harbor racists beliefs, and intentionally levy political consequences on the targets of that racism.

In this article I provided the framework for assessing the institutional constraints that allow for insidious racism to occur. Well-established forms of racism, such as aversive, laissez-faire, color-blind, and symbolic forms, rely primarily on individual behaviors that are influenced by unconscious attitudes toward people of color. These individual behaviors are not intentionally racist, but are effectively racist. As such, solutions to eradication of these types of racism have focused primarily on education, exposure, and restoration. Contrarily, insidious racism relies on intentionally racists behaviors. Insidious racists will engage in negative and discriminatory behaviors when their racist actions are not easily attributable to them. Thus, this extant form of overt racism is not only dependent on the conscious and racist attitudes of individuals, but it is also dependent on the opportunity structure for overt racism to occur.

Insidious racists understand that bigoted people are personae nongratae in today’s America, and they do not want to assume such a label. As such, their racist behaviors are only showcased in environments where institutional and administrative oversight—and therefore the probability of societal blowback from being outed as a racist—are low. These strategic movements by intentional racists limit the study of intentionally and insidiously racist actions to cases where the racist actions were exposed through insider revelation or investigation (such as the cases reviewed in this article). As previous research has shown for decades, measuring levels of racism accurately is near impossible today due to the tendency of most people to protect their own images when surveyed, even if they harbor racist feelings (Picca and Feagin, 2007; Wellman, 1977). However, the study of insidious racism is important at present, and aids policy makers in identifying where institutional oversight or administrator discretion are at issue. Through the study of insidious racism, currently exploited policy can be upgraded, and new policy can have built-in measures to protect from exploitation by insidious racists.

At all levels of government, the magnitude of institutional oversight and the responsible parties for administrative oversight are designed by legislators. Thus, in writing and enacting new policies, legislators must incorporate sufficiently high levels of institutional and administrative oversight that create environments where insidious racism cannot flourish. Further, the interventionist beliefs of administrators matter in creating environments where insidious racism does not thrive. Given a scenario in which legislators have designed high institutional oversight, if the designated administrator responsible for oversight (for example, a judge) believes the government should be very limited in the dealings of private citizens, insidious racism can still occur. As revealed in the case studies of Wells Fargo and Los Angeles, environments with insufficient levels of institutional and administrative oversight can result in the hyper exploitation and maltreatment of people of color. Taken together, these national and local cases represent a social scientific sample of insidious racism through their ability to provide insight into the scope conditions of insidious racism (Elman et al. 2016). Further, the discussed deviant cases point toward mediating factors previously unrepresented in contemporary theories of racism (Seawright and Gerring, 2008). These mediating factors help explain negative socioeconomic outcomes based on race in environments governed by perceived race-neutral policy. Through the employment of this framework of institutional constraints, future researchers can identify policy areas that result in racist outcomes due to insufficient institutional and administrative oversight and insidious exploitation. Researchers might reveal that there are not enough checks in the institutional design, or that administrators are not empowered enough to prevent insidious racism. Through this identification, researchers can further inform legislators of potential changes to institutional designs that can correct the environment to prevent future occurrences of insidious racism.

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analyzed.