Property taxes are one of the main sources of revenue for state and local governments, making up about 31.5 percent of total U.S. state and local tax collections as of fiscal year 2016.[1] Most property tax revenue flows to local governments, and localities are reliant on property taxes to fund government services such as public education, making up about 72 percent of all local tax revenue in fiscal year 2016.[2]

The property tax base is an important element of state and local tax codes, as property taxes alter business investment decisions and where people decide to live. While most people are familiar with residential property taxes on land and structures, known as real property taxes, many states also tax tangible personal property (TPP) owned by individuals and businesses.

Tangible personal property (TPP) comprises property that can be moved or touched, and commonly includes items such as business equipment, furniture, and automobiles. This is contrasted with intangible personal property, which includes stocks, bonds, and intellectual property like copyrights and patents.

Taxes on TPP make up a small share of state and local tax collections, but create high compliance costs, distort investment decisions, and are an archaic mode of taxation. This paper reviews the history and administration of tangible personal property taxation, examining how states have reformed their tax levies on TPP over the last 10 years. It will provide recommendations on how policymakers can alleviate TPP tax burdens while being conscious of how TPP taxes provide localities with needed revenue, using previous state experiences as a guide. This will give state and local governments a path forward to eliminate TPP taxes from their tax codes over the long run.

In the United States, levies on personal property emerged in tandem with taxes on real property. Property taxes originally approximated a tax on wealth more than modern property taxes do, as taxes on personal property have waned.[3]

As the administrative burden of assessing personal property grew more complicated, policymakers in the 19 th century sought to limit property taxes to real estate and certain types of personal property, such as inventory and machinery.[4] Individual property owned for personal use was gradually excluded from the tax base in the 20 th century, with the focus shifting almost entirely to TPP owned by businesses.

Internationally, countries shifted from taxing tangible personal property: across the 36 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, only seven countries levy taxes on personal property: Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[5]

Over time, the American personal property tax base was eroded as states provided exemptions for different types of TPP. For example, agriculture, manufacturing, and renewable energy firms are often exempt from TPP levies. Many states offer exemptions for economic development if firms meet certain requirements, such as number of new jobs created or a set amount of investment in a locality.

For instance, Maryland permits local governments to provide a credit for expanding manufacturing facilities.[6] Similarly, Idaho allows counties to exempt TPP that is part of an investment of at least $500,000 in a new manufacturing plant for up to five years.[7]

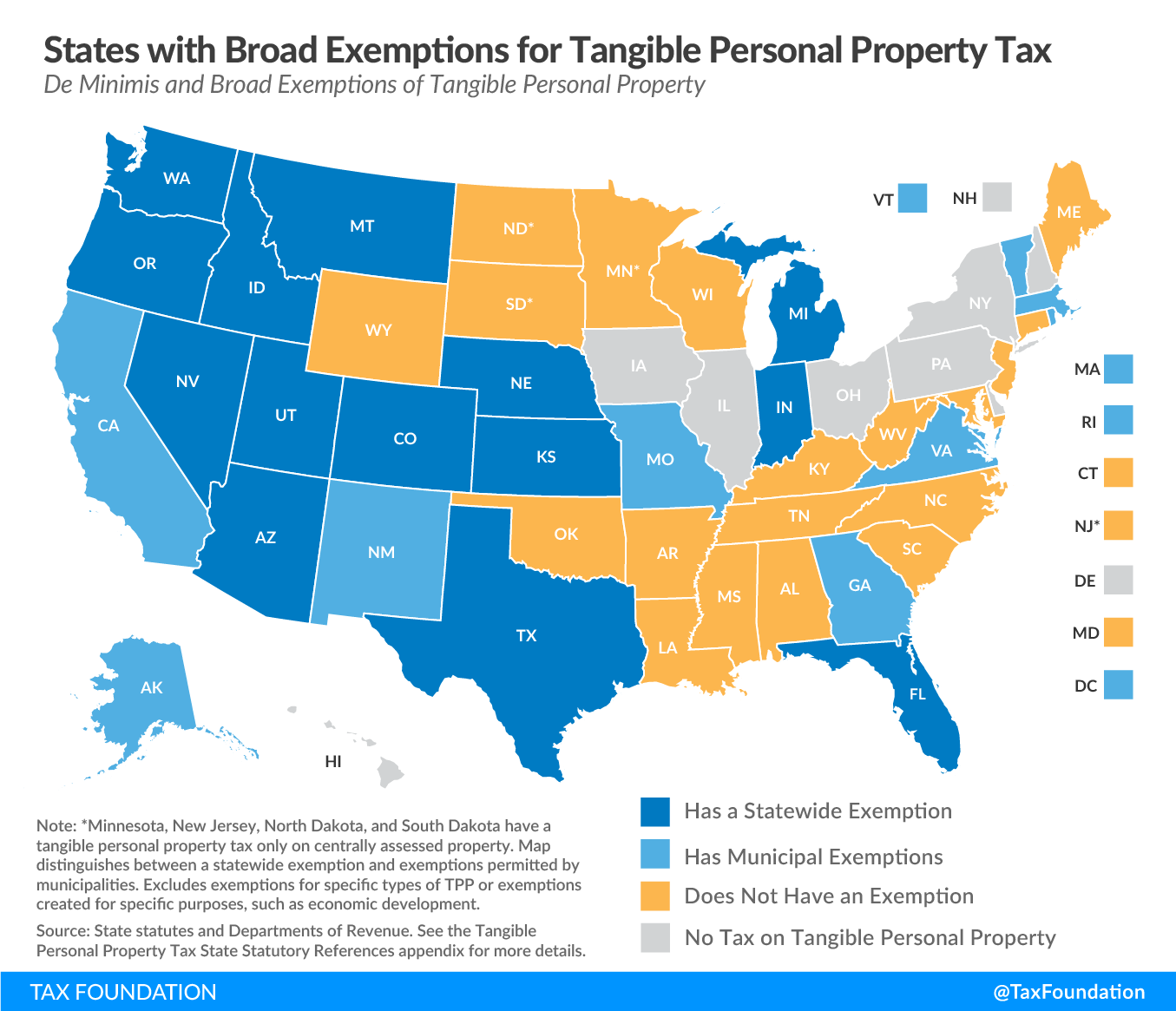

Seven states (Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) exempt all TPP from taxation, while another five states (Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, and South Dakota) exempt most TPP from taxation except for select industries that are centrally assessed, such as public utilities or oil and natural gas refineries.

Taxes on TPP are levied mostly by local governments, but they are regulated at the state level. There is much variation in how TPP is taxed. Property classifications, assessment ratios, and exemptions are often established by the state, with localities opting to tax TPP within the boundaries set by the state government. Twenty-three states permit municipalities to reduce the tax owed on TPP, while 27 states do not provide this option (see Table 2 in the Appendix).

The process for calculating and remitting TPP tax is complicated and varies depending on the state. Firms must first determine which property is eligible for taxation, which varies across states, counties, and municipalities. States usually exclude personal use property from TPP tax, instead focusing on business property.

Some states tax durable assets like motor vehicles, watercraft, and aircraft owned for personal use, as these assets have liquid secondary markets and avoid many of the administrative challenges of assessing other personal use property. For property that is not excluded or exempt from the TPP tax base, TPP tax liability is calculated by first determining the assessed value of the property and multiplying it by the assessment ratio for that class of property. Assessment ratios typically reduce the value of the property subject to tax, lowering a taxpayer’s tax liability.

Assessment ratios may also be higher for TPP than for real residential property. Fifteen states impose different assessment ratios for TPP than for real property. This means that TPP has a separate assessment ratio to determine the property value that will be subject to the property tax millage. States may also levy different assessment ratios for separate types of TPP. For example, South Carolina uses an assessment ratio of 5 percent for farm machinery and equipment, compared to 10.5 percent for most other TPP.

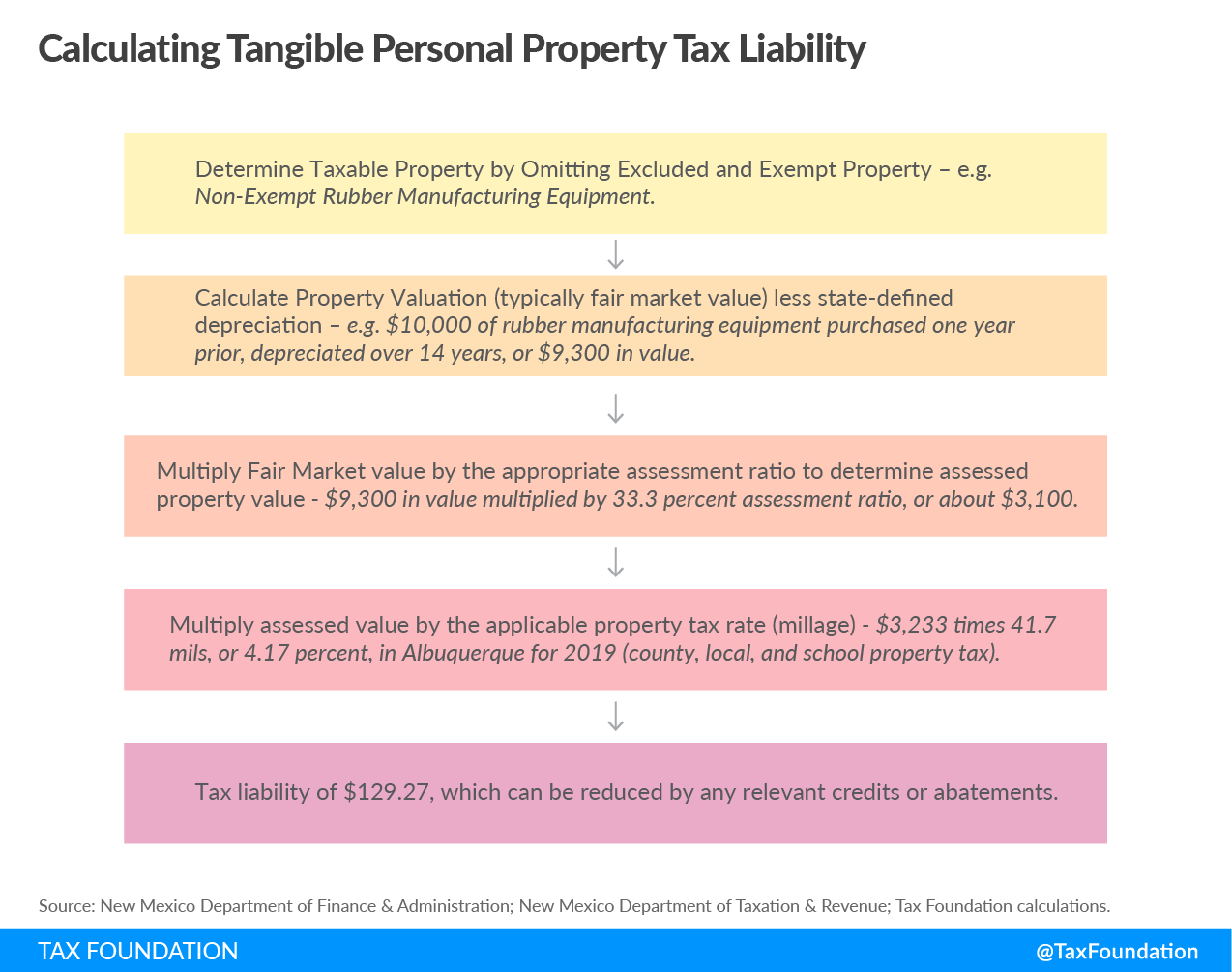

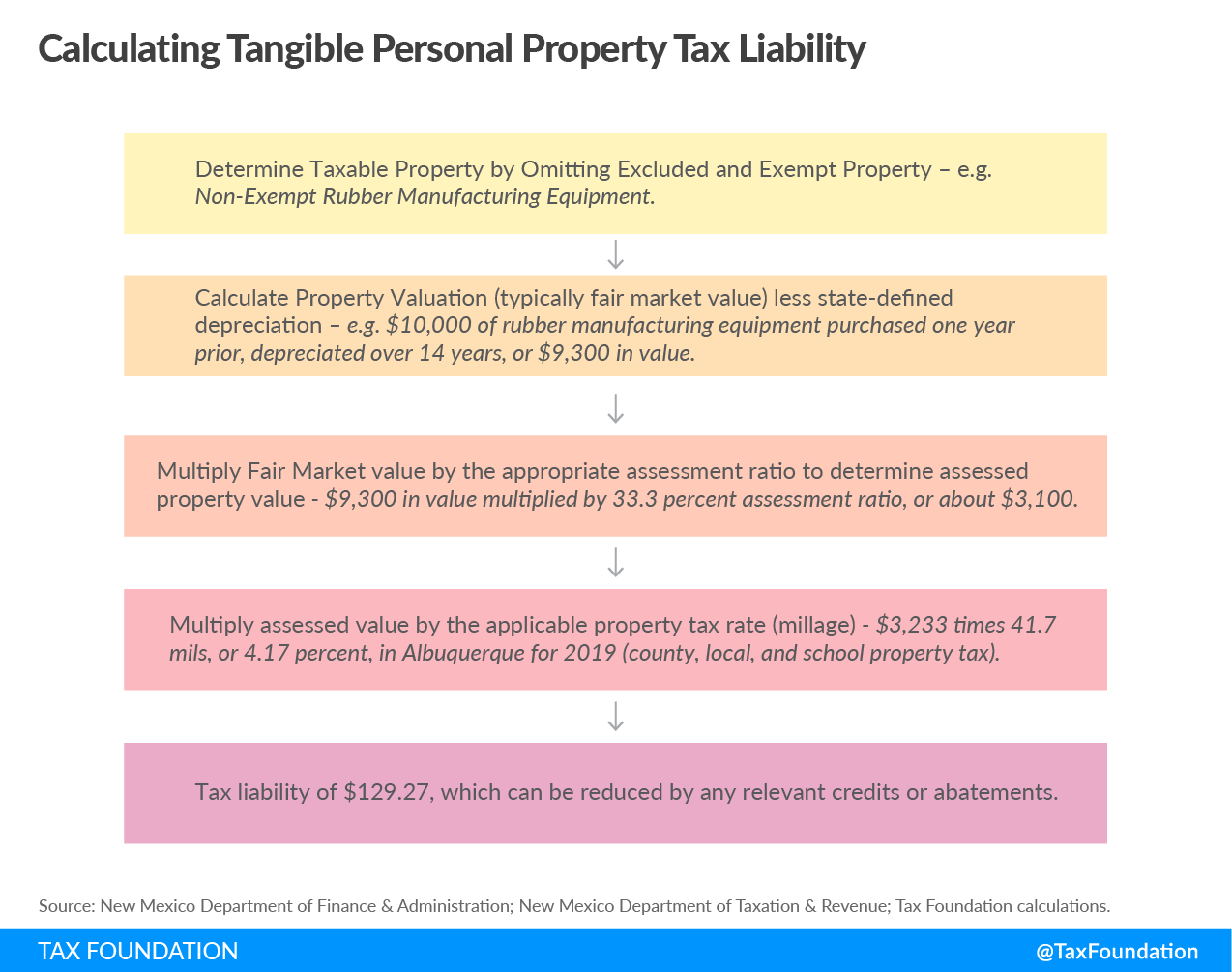

Figure 1.

Take, for example, a rubber factory in New Mexico. The business must first determine if it holds TPP subject to tax. New Mexico taxes TPP that is maintained by a business for which it took a federal tax depreciation Depreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. in the previous tax year. The business’ rubber manufacturing equipment may therefore be taxed, unless it is used for an exempt purpose. If the business is the lessee of a metropolitan redevelopment property project, for example, the TPP may still be exempt for up to seven years from acquisition.[9]

Once the business determines its taxable property, it must value the property. New Mexico appraises property by examining the cost of acquiring the property, the value of the property if sold, and the present value of the income generated by the property.[10] For machinery and equipment, the cost approach is most often used.[11]

The property value is then depreciated with the straight-line method using state-defined depreciation schedules.[12] The straight-line method of depreciation is calculated by dividing the value of the asset by the number of years it is expected to be used and subtracting that amount from the value of the asset each year.[13] This value is multiplied by the state’s uniform assessment ratio, which is set at 33.3 percent for all property, to arrive at the property’s taxable value.[14]

The taxable value is multiplied by the millage, which is the applicable property tax rate. States may either apply the same tax rate across real and tangible personal property or may levy different tax rates for different types of property. Levying different tax rates on TPP is one way that local governments may raise additional revenue on nonresidential property and favor specific taxpayers.[15]

Once TPP tax is calculated, taxpayers may reduce their liability through tax credits and abatements. Credits for TPP tax are commonly used to incentivize economic development. In Maryland, for example, localities may grant a tax credit A tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. for new or expanding manufacturing facilities under certain conditions.[16] Abatements, which reduce tax liability after it has been assessed but before it has been paid, are another way states and municipalities may reduce TPP tax burdens. Nevada uses abatements for businesses operating in economic development zones, for instance.[17]

Like the limitation regimes established for real property, state governments have instituted limits on the growth of personal property taxes. Property taxes may be limited through three methods: assessment limits, levy limits, and rate limits.[18]

Assessment limits cap increases in TPP tax produced through a rise in assessed value.[19] While real property often appreciates, personal property usually depreciates in value over time.[20] Assessment limits are therefore less applicable to personal property, as the property is unlikely to require a limitation in the growth in assessed value.

Personal property tax regimes may be subject to rate limits, which constrains the ability of state and local governments from raising tax rates above an absolute threshold or above a fixed growth rate. This limits revenue growth from personal property taxes through deliberate increases in tax rates. Rate limits are more common for TPP and are often defined statutorily at the state level.

Levy limits impose restrictions on the total amount of revenue collected from property taxes. Levy limits may apply to real property and personal property. In Washington, the state constitution limits tax from real and personal property to 1 percent of total property value unless voters approve a higher percentage.[21]

Property taxes comport to the benefit principle and are economically efficient when levied on real property.[22] Real property taxes fund state and local government services, and they are a comparatively transparent method of taxation. Included in the real property tax base is land, which generates economic rents and is an efficient source of tax revenue.

Landowners cannot move their land and avoid tax liability and will fully bear a tax imposed on land. Taxes on real property are also imposed on buildings and other improvements on land, which affects the marginal decision to improve and build on the property; evidence suggests that property taxes are a significant factor in business location decisions.[23]

The relative efficiency and transparency of real property taxes can be contrasted with taxes on TPP.

Tangible personal property taxes are a type of stock tax on the value of a business’ tangible assets. These assets are used to generate a return, which is reduced by the TPP tax. This influences investment decisions, dissuading firms from making the marginal investment in their enterprises.

Imagine, for example, a manufacturing firm considering a new investment in machinery that faces a 0.5 percent effective TPP tax rate annually. If the machinery can be fully expensed and depreciates at 5 percent per year, the effective tax rate on the marginal investment in machinery is 6.67 percent due to the TPP tax.[24] This means that an investment that breaks even—earning a 0 percent net return and covering costs in present value—faces a 6.67 percent tax rate. In other words, 6.67 percent of the gross return from the marginal investment covers the TPP tax. A TPP tax dissuades firms from making new investments.[25]

Like other wealth taxes, TPP taxes are a poorly targeted form of capital taxation.[26] Ideally, the tax code exempts or lightly taxes a normal return–compensation for deferring consumption–and targets super-normal returns earned above that threshold. Super-normal returns generated by economic rents, innovative business models, and luck are less sensitive to taxation and are a more efficient source of tax revenue.[27]

A tax on tangible personal property, by contrast, disproportionately targets normal and low rates of return. For example, machinery producing a 4 percent return and facing a 0.5 percent effective TPP tax rate yields a 12.5 percent effective tax rate, while machinery producing a 10 percent return only yields a 5 percent effective tax rate from the same TPP tax.

TPP taxes discourage investment at the margin while poorly targeting super-normal returns, slowing economic growth, and creating a poorly targeted tax on returns to capital.

In addition to being a poor form of capital taxation, taxes on TPP are nonneutral. TPP is often treated differently from real property, with separate assessment ratios and millage rates.

As states have narrowed the TPP tax base by exempting personal-use property, expanding de minimis exemptions, or providing credits for favored activity (such as economic development), this has increased the variability of how TPP is treated in state property tax codes. Certain kinds of TPP, or TPP used in ways that make them ineligible for exemptions, credits, or abatements, are impacted more by property taxes.

Businesses attempt to avoid TPP tax by altering their investment and purchasing decisions. For example, a firm may avoid purchasing automated machinery in favor of using additional labor if the machinery is subject to a property tax. There is evidence that the elimination of TPP taxes increases investment in capital. In Ohio, policymakers exempted manufacturing equipment from the state’s TPP tax, resulting in greater capital investment and a shift from labor.[28] Increased capital investment improves labor productivity, raising wages higher than they would otherwise be for workers.

Alternatively, firms may shift their activity to take advantage of tax preferences for TPP, such as moving to municipalities where tax rates are lower for the TPP a firm owns. In some states, TPP is assessed on a specific “snapshot” date, while others may pro-rate TPP tax assessment for ownership of property owned for less than one year. For example, a piece of equipment owned for six months would have a 50 percent pro rata assessment. For states that use a “snapshot” date for assessment, firms may defer investments until after TPP tax has been levied for the tax year, with the goal of disposing of the property prior to the next time TPP taxes are levied.[29]

Tangible personal property taxes are a type of tax on business inputs, as property such as machinery, equipment, and inventory are part of a firm’s production process. Firms may pass along the tax in the form of higher prices when goods or services are sold in the production process. This may conceal the impact of the tax on consumers, as consumers may pay higher prices as a result of a tax on TPP.

Taxes on TPP are “taxpayer active,” meaning that taxpayers must determine the tax liability that they owe, accounting for the depreciable value of their taxable property, the relevant assessment ratios and millage, and applicable credits, abatements, and refunds for which they are eligible. This increases the cost of complying with TPP taxes.

Compliance costs are higher in states that have different assessment ratios and millage rates for different types of TPP. Fifteen states use separate assessment ratios for residential property and TPP (see Table 2 in the Appendix).

Firms with different types of TPP across multiple municipalities may have to sort through dozens of different exemption requirements, assessment ratios, millage rates, TPP declaration forms, and relevant tax credits, which amplifies the cost of compliance.

Some states have made efforts to reduce the compliance burden on firms. Nevada’s Tax Commission, for example, may exempt TPP if the annual tax is less than the cost of collecting it.[30] This also helps reduce administrative costs for the state.

Twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia simplify part of the administration of TPP taxes by offering a uniform tangible personal property declaration form that can be used across the state. In the other 16 states, firms must use locality-specific declaration forms and processes to calculate and remit their TPP tax liability. For firms with TPP in many jurisdictions, this is a source of tax complexity and a high cost of compliance.

Of the states with data available for personal property, personal property made up 11.27 percent of the average state property tax base in 2006. This fell to 10.15 percent of the average state property tax base in 2012 and to 9.98 percent of the average state property tax base in 2017 (See Table 1).[31] States are relying slightly less on personal property as part of the property tax base.[32]

Source: Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, “Significant Features of the Property Tax.®”

Since 2006, states like Connecticut and Kentucky have markedly increased the relative share of personal property in their property tax bases, while Colorado, Georgia, Maine, North Carolina, and Utah have markedly reduced the relative share that personal property makes up in the property tax base.

While no state has eliminated TPP outright from its property tax base over the past decade, states have expanded their use of de minimis exemptions and raised exemption thresholds for TPP tax. This reduces the number of firms subject to TPP tax or lowers tax liability for firms which owe TPP tax and may explain some of the reduced reliance on TPP in state property tax bases.

De minimis exemptions provide relief for small firms by eliminating their tax liability if they remain below a valuation threshold for their tangible personal property. These exemptions lower compliance costs for firms with a small amount of otherwise taxable TPP.

Figure 2.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Indiana, for example, recently raised its de minimis exemption from $20,000 to $40,000 in business personal property per county and prohibited counties from collecting TPP tax filing fees from businesses that file but do not have a tax liability.[33] Indiana originally implemented its $20,000 de minimis exemption in 2015, and 89,749 taxpayers took advantage of the exemption.[34] An additional 28,300 exemptions were projected by the Indiana Legislative Services Agency as a result of the increase in the exemption threshold.[35]

Since 2012, Utah, Colorado, Idaho, and Indiana have enacted or expanded their de minimis exemptions. Utah exempts individual items of TPP with an acquisition cost of $1,000 or less in addition to exempting TPP with a fair market value under $10,800.[36] In Colorado, the legislature added a state income tax credit to reimburse taxpayers’ TPP tax between $7,001 and $15,000, effectively raising the state’s $7,700 TPP exemption.[37]

As states consider de minimis exemptions for TPP, policymakers should consider making the exemption threshold also a filing threshold. This reduces compliance costs for firms, as firms under the threshold may have to file in many localities if filing requirements remain in place when firms are under the de minimis threshold. Indiana, for example, previously required taxpayers to file a TPP tax return and pay filing fees even if they qualified for exemption. In April 2019, the state prohibited counties from collecting TPP tax filing fees but kept the filing requirement for exempt taxpayers.[38]

Most state exemptions are indexed to inflation Inflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . Oregon’s de minimis exemption was originally set at $12,500 but has since risen to $17,000.[39] Indexing exemption thresholds ensures that firms are not pushed above the threshold over time due to inflation. States that have not indexed their exemption thresholds should consider doing so, which will help maintain the value of the exemption for firms over time. Texas, for instance, should index its TPP de minimis exemption of $500, after raising their de minimis exemption to cover more firms that own TPP.[40]

In addition to de minimis exemptions, some states provide broader exemptions for a certain amount of TPP for all taxpayers. Florida, for example, provides a $25,000 exemption for all property in the county where the property is used for business purposes.[41] Universal exemptions avoid the tax cliff that de minimis exemptions face and reduce the TPP tax burden for more firms.[42]

Idaho enacted a $100,000 exemption on personal property taxes in each county per taxpayer.[43] All TPP worth less than $3,000 is also exempt, which works like Utah’s exemption for individual items of TPP costing less than $1,000. Utah and Idaho’s exemptions show that states may pair a broad de minimis or universal exemption with an exemption for individual pieces of TPP under a certain value.

For example, a firm in Idaho may have $110,000 in TPP. The first $100,000 is exempt from tax; individual items worth less than $3,000 may also be exempt even above the $100,000 threshold.[44] Washington takes a similar approach by exempting $15,000 of TPP for heads of household, corporations, and limited liability corporations while exempting personal property worth $500 or less from property tax.[45]

Nebraska also exempted the first $10,000 in personal property from taxation in 2015, and included a provision reimbursing municipalities for lost tax revenue from the exemption.[46] Montana has a limited TPP tax exemption A tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. for commercial and industrial TPP, which is classified as a distinct type of property. The first $100,000 of commercial and industrial TPP is exempt from TPP tax. Prior to enactment of the $100,000 exemption, Montana had a $20,000 de minimis threshold. By raising the limit and making the exemption available to all firms, Montana reduced the number of firms exposed to TPP tax liability.[47]

One approach Michigan has taken is to create two separate exemptions: one for eligible manufacturing TPP and a de minimis exemption on TPP worth less than $80,000. To replace the revenue lost from these exemptions, Michigan established an Essential Services Assessment (ESA). The ESA is a tax on the TPP using the exemption for eligible manufacturing personal property with a millage rate ranging from 0.9 mills to 2.4 mills, resulting in a lower tax burden for most taxpayers with TPP.[48]

States have made progress in reducing TPP tax burdens over the past decade, but there remains room for reform. The most fruitful areas of reform include exempting major business inputs such as inventory, machinery, and equipment from TPP tax, which make up a large component of TPP tax bases. Additionally, states should permit localities to reduce TPP taxes in their jurisdictions and streamline TPP depreciation rules, simplifying one aspect of TPP tax administration.

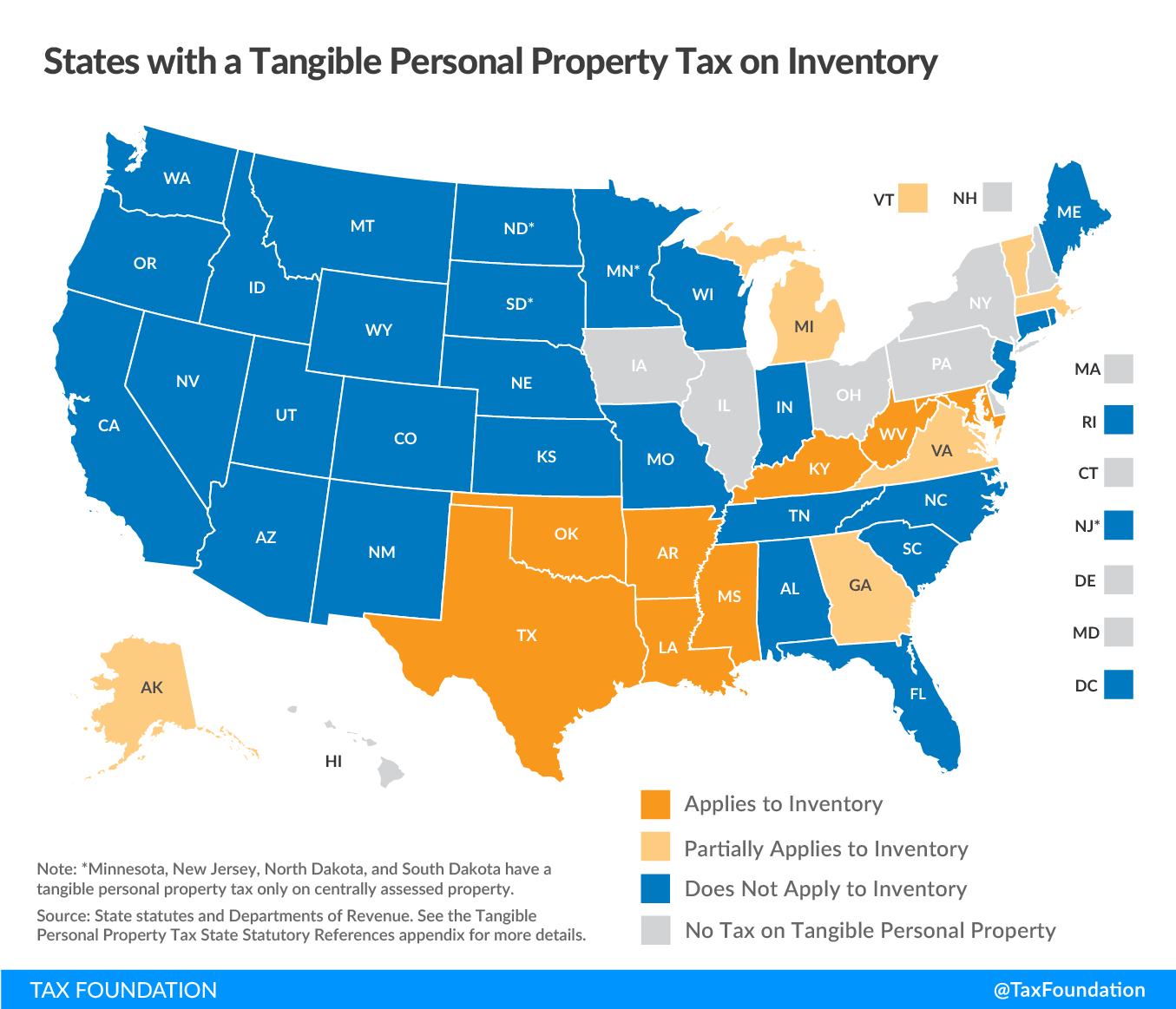

Fourteen states levy TPP taxes on inventory in some form. Eight states fully tax inventory, while six states tax inventory partially but exempt certain types of inventory or exempt inventory from property tax at the state level. For example, in Georgia, inventory is exempt from state property taxes, but localities may tax inventory. Ninety-three percent of counties in Georgia partially exempt inventory using a freeport exemption ranging from 20 percent to 80 percent of the value of the inventory.[49] In Michigan, inventory is exempt from property tax, except for inventory under lease.[50]

Figure 3.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Taxes on inventory are nonneutral, as businesses with larger quantities of inventory, like manufacturers, are disproportionately burdened by the tax.[51] Businesses with little to no inventory escape this form of property taxation, despite using local and state government services like firms with larger amounts of inventory.

Inventory taxes, like many other taxes on TPP, are often locally assessed and are a revenue source for localities, making it a challenge to replace the revenue when states exempt inventory from the property tax base.

States with property taxes on inventory are considering ways to eliminate the burden on firms while not depriving municipalities of the tax revenue. Kentucky, for example, enacted a state income tax credit that offsets TPP tax paid on inventory. The credit is being phased in from 2018 to 2021, with the credit amount rising by 25 percent increments every tax year.[52] Taxpayers will still need to calculate and remit their TPP tax liability but will find relief through a reduced state income tax liability. The tax credit is nonrefundable, meaning that taxpayers can only reduce state income tax liability to zero. Beyond that amount, taxpayers will not find additional relief from TPP tax on inventory.

Machinery and equipment make up a large portion of state TPP tax bases and are key business inputs for firms.

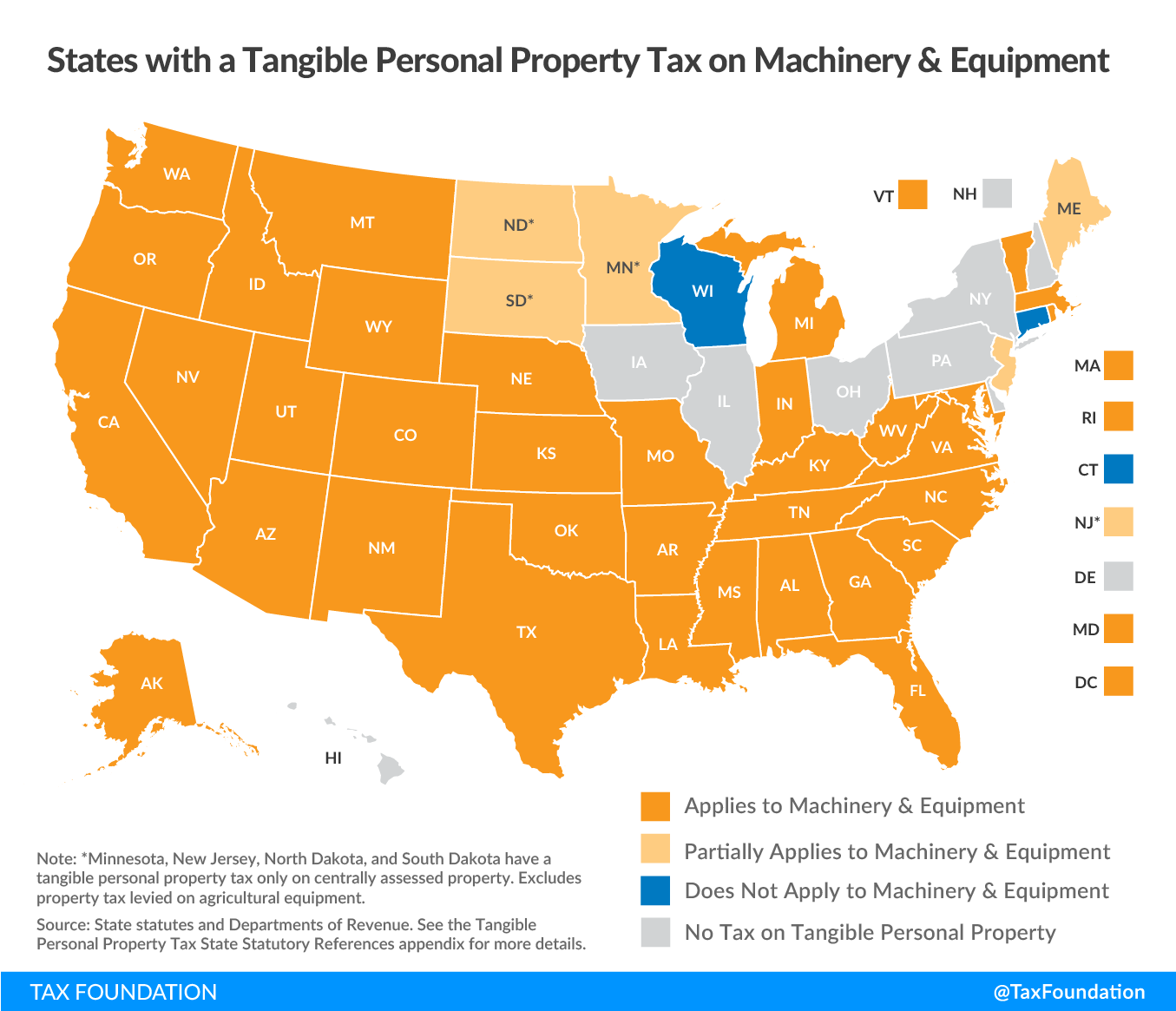

Figure 4.

Thirty-six states levy TPP taxes on machinery and equipment. Often, agricultural machinery and equipment will be granted lower assessment ratios or millage rates than other forms of TPP. For example, Missouri uses a 12 percent assessment ratio for farm machinery but a 33.3 percent ratio for most other TPP.[53] Similarly, South Carolina assesses farm machinery and equipment at 5 percent when most TPP is assessed at 10.5 percent of value.[54] Other states, like Utah, exempt farm machinery and equipment outright.[55]

Some states exempt all machinery and equipment from the property tax base. Like inventory, these forms of property are critical to many firms and are a large determinant of businesses’ TPP tax liability in manufacturing and related industries. To smooth out the impact of exempting machinery and equipment, some states only exempt property acquired after the exemption is enacted. Kansas, for example, did so when enacting an exemption of commercial and industrial machinery in 2006.[56]

As firms replace machinery that depreciates over time, more property becomes subject to the exemption. Tax revenue gradually declines, giving the state and localities an adjustment period to replace the lost revenue. This should be an approach that other states consider when balancing revenue stability for localities with the repeal of TPP taxes on machinery and equipment.

Another option to reduce TPP tax burdens is to authorize localities to reduce TPP tax rates or exempt types of TPP. Twenty-three states permit localities to partially or fully exempt firms from TPP taxation. This gives municipalities greater control over their property tax base while transitioning them from relying on TPP taxes for revenue.

State and local governments should carefully consider the trade-offs involved when exempting or eliminating TPP tax. While taxes on TPP violate the principles of sound tax policy and would not exist in an ideal tax system, local governments rely on the tax revenue generated by taxes on TPP. State governments have considered tax swaps to resolve this problem in other contexts, but these schemes are often difficult to implement.[57]

Both Kentucky and Louisiana have tried to resolve the problem of lost revenue by creating state income tax credits to eliminate a firm’s inventory tax liability. Local governments still receive tax revenue, with the state government refunding the levy back to businesses.[58] In 2016, the tax rebate cost Louisiana about $225 million.[59] Louisiana is exploring possible local-for-local tax swaps, given the complexity of the current rebate system.

Slow phaseouts over multiple years can help mitigate the problems associated with a loss of revenue. Vermont, for example, authorized cities and towns to exempt inventory and other TPP from local taxes, with the option of phasing in the exemption up to 10 years.[60] From 2013 to 2018, the number of municipalities taxing inventory has fallen from 34 to seven (about 3 percent of all municipalities). The same trend occurred with the taxation of machinery and equipment, with the number of municipalities levying those taxes dropping from 62 to 45 (about 18 percent of all municipalities).[61] This shows that localities can make headway eliminating taxes on inventory while finding alternative revenue sources over time.

When localities are permitted to reduces taxes on TPP, there is evidence that this increases revenue growth for other types of taxes. In Pennsylvania, counties that repealed their taxes on personal property between 1978 and 1990 experienced greater growth in revenue from their real estate taxes than counties that kept a tax on personal property.[62] Higher tax revenue from other sources may help localities as they transition from TPP taxes, but would not fully cover the decline in revenue in most cases. Instead, local governments should consider local-for-local tax swaps to maintain revenue stability.

State and local governments provide depreciation schedules for the purposes of TPP that is usually different from the federal treatment of the property for income tax purposes. Many states use straight-line depreciation schedules when calculating TPP tax.

Navigating different depreciation schedules for income tax and property tax is a source of tax complexity for businesses, and policymakers should consider ways to simplify the process of depreciating TPP. This is especially true in states that do not conform to depreciation rules for income tax purposes with the federal income tax, as firms must calculate applicable depreciation more than once to determine income tax liability and TPP tax liability.[63]

One method some states have taken to improve the tax treatment of personal property is improving how taxable TPP is depreciated. In 2011, Arizona accelerated the depreciation provided for certain classes of taxable business property, and the legislature extended the accelerated depreciation in 2017.[64] This approach shortened the depreciation schedule, lowering tax liability on TPP.

Shortening depreciation schedules is another lever for states to lower TPP tax burdens on firms. The schedules could also be adjusted over time to give localities an opportunity to adapt to the lower revenue raised from the tax.

The taxation of tangible personal property by state and local governments is a blight on a relatively efficient and transparent type of tax. Property taxes, when properly structured, conform to the benefit principle by supporting government services used by property owners in a transparent manner.[65]

Taxes on tangible personal property, on the other hand, increase the complexity of state and local tax codes, discriminate against taxpayers based on their capital structure, and change economic behavior by incentivizing taxpayers to modify their property ownership to avoid the tax. Efforts by some states to exempt major types of TPP, raise de minimis exemption thresholds, and provide a local option to reduce TPP taxes show that progress is possible, despite the challenge a reduction or elimination of TPP taxes poses to state and local budgets.

To establish buy-in among municipal stakeholders, states should consider options to consider the revenue lost from eliminating TPP taxes or expanding TPP tax exemptions. State-for-local tax swaps, such as providing state income tax credits to firms that pay TPP taxes, are challenging to effectively administer and may not unanchor localities from their reliance on TPP tax revenue. Instead, states should grant localities greater authority to reduce TPP tax burdens and replace the lost revenue elsewhere. Local option tax reductions are a more promising approach and have been shown to work in states like Vermont over several years.

With some courage, states have an opportunity to rid themselves of an antiquated tax, streamlining their property tax codes and making their tax systems more consistent with the principles of sound tax policy.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Source: State statutes and state departments of revenue.